(This is the second half of an earlier post. If you don't read it, you will understand nothing).

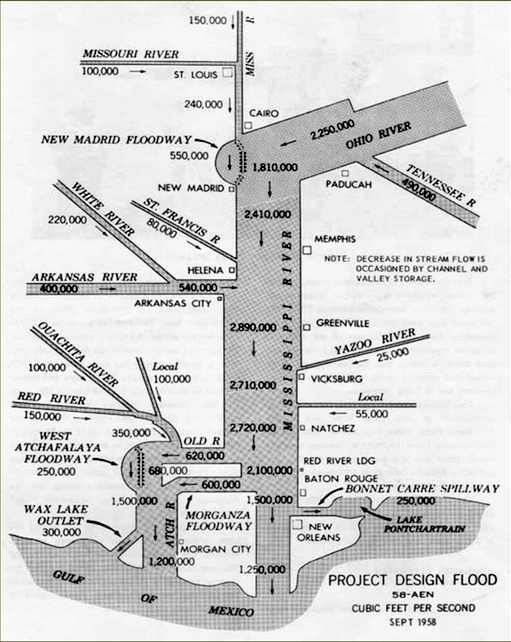

Phyllis talks a lot about “the wrong kind of earthquake”. The wrong kind of earthquake in the central United States would strike on a work day when all of the unreinforced masonry buildings are full of people (American homes tend to be wooden-frame and are much safer). It would take place in winter, when temperatures in the Midwest are below freezing and demand for natural gas in the Northeast is high. If the epicenter were near New Madrid, it would kill thousands of people in Memphis alone. Hundreds of thousands would be left homeless, and entire districts (like happened in Christchurch) would be permanently condemned. The river might shift its course. Vast tracts of farmland, which depend on changes of grade of a few feet for irrigation, would go fallow. No one in the region would have power or fresh water for days.

Such a quake would damage or destroy the Mississippi bridges over hundreds of miles, cut the natural gas pipelines that are a critical source of energy to the Northeast, and release a stew of toxic chemicals into the river. It would shut down the Federal Express hub at Memphis and flatten large numbers of the rickety tilt-up warehouses, packed with inventory, that have grown up like mushrooms around the Memphis facility as companies try to out-compete each other in shipping speed.

Liquefaction would damage long stretches of road beyond repair. The trucking and freight industries would be completely disrupted, in the old-fashioned sense of that word. A major earthquake would shut down the vast steelyards near Blytheville, AK that are one of the chief American producers of structural steel, the kind you need to rebuild all the structures destroyed in an earthquake. Even if it didn't jump its bed, the Mississippi River would be closed to navigation for weeks. Communities across the central United States would be left stranded without water, power, fuel, transportation, or emergency services for periods ranging from days to months.

And when the rains came in the spring, the river would pour through every damaged levee.

I ask Phyllis if there's a “right kind of earthquake” in her estimation. Phyllis is not bloodthirsty, but she's pragmatic. You can't get people to fund preparedness without political cover. She suggests a summertime weekend tremor, something in the 6.5 range, with no casualties but enough pep to cause property damage in the low nine figures. Something to wake people up.

Earthquake preparedness in the United States is the job of a minor alphabet soup of agencies: the National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program (NEHRP), its parent National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

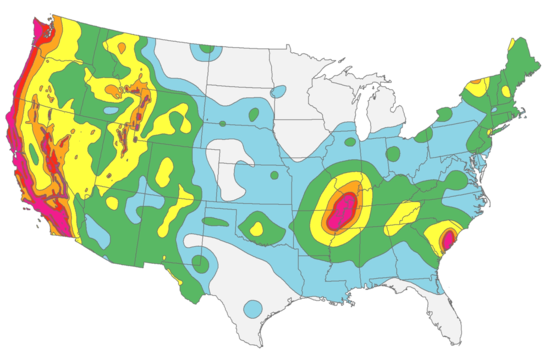

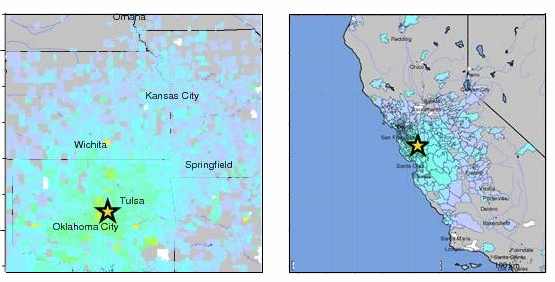

It's that last organization that has to turn conjecture and ignorance into numbers for communities to plan against. Their analogue to the Project Design Flood is a set of seismic hazard maps, updated every six years, that provides a probabilistic estimate of maximum shaking intensity. The maps are the product of extensive study, historical analysis, consensus and a healthy dose of guesswork. They serve as input for local building codes, awareness programs, and a planning tool called HAZUS.

HAZUS is a federally-mandated software contraption that tries to model the physical and economic impact of floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes. It takes information about geology, population and the built environment as input, and spits out damage maps and estimates of economic impact.

HAZUS is also a layer cake of assumptions about geology, structural engineering, soil science, economics and even demographics (for example, the model assumes Hispanic populations will be more reluctant to re-occupy buildings after an earthquake because of their heightened awareness of building collapses after quakes in Latin America). Each layer's tentative conclusions are fed as input to the layer above. Running a full HAZUS scenario can take months and requires high amounts of domain expertise.

The very richness of detail in the model encourage a false sense of understanding, especially when disseminated to a non-expert audience. Like the Project Design Flood, HAZUS scenarios are an attempt to tame the wild uncertainty of nature and bring it within the purview of political planning. But there's always the risk that we're learning more about the model than the world, or at the very least overtraining on the tiny sliver of history available to us.

Ste. Genevieve, MO

We roll on to Ste. Genevieve, a beautiful community of old French houses, and the oldest settlement on the west bank of the Mississippi River. There's a Ship of Theseus feeling to many of these historic Midwestern sites, which tend to migrate with time. Ste. Genevieve, established in 1750, moved to its present uphill location in 1785 after the settlers discovered what had kept the original riverfront site so remarkably flat and treeless. The town center has the feel of a European village, with house after house that is over a century old. The oldest houses are built in a distinctive French style within a framework of sturdy wooden posts. Whatever faults the Acadians may have had, they did not underbuild.

Here and there, a low ranch-style bank or insurance building interrupts the flow of the village to remind everyone that the seventies happened. Downtown is full of brick buildings that have been built since the earthquake, including a very tall brick cathedral from 1896. Ste. Genevieve once made a lot of money selling grain to New Orleans and other towns down the river, where the climate was too hot to grow wheat. Much of that money has gone to pay for lovely cornices and decorative ledges, all of which are going to fall on people's heads when the quake comes.

Kitty-corner from the death trap cathedral is the Old Brick House, which claims to be the only unreinforced masonry structure to have survived the 1811 quake. There are rumors, though, that if you look at the beamwork in the cellar you'll see clear traces of a circular saw, invented decades after the earthquakes. Somebody clandestinely rebuilt the place. The Old Brick House is a house of lies.

From Ste. Genevieve we set a course south to New Madrid. The temperature has been dropping and the wind is picking up for real. By the time we stop for lunch at a windswept rest area, it's an icy forty-two degrees and the big cooler Phyllis brought is looking unnecessary. We spread its contents across a picnic table, assemble sandwiches with numb fingers, and race back to the shelter of the cars to eat.

Something labeled a ‘Party Bus’ pulls in nearby and disgorges a group of grimly intoxicated women in sweatpants. They make a beeline for the restrooms. The party don't stop just because it's freezing.

The interstate takes us south through deposits of a material called St. Peter sandstone, which our packet describes as ‘a very competent limestone’, renowned for its purity of composition. It has grains of a remarkably uniform size, so it finds application in household cleansers, industrial processes, fracking—wherever the finer grits are found. My geologist colleagues are actually snapping pictures of the stuff as we pass through the larger road cuts at sixty miles per hour. It is my first encounter with a celebrity sandstone.

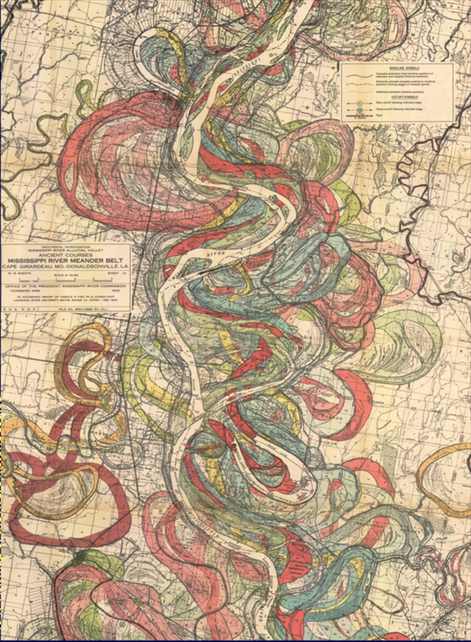

Phyllis tells us to feast our eyes while we can. We’re leaving the Benton Hills and about to enter a vast feature called the Mississippi Embayment, a tongue of flat land that extends northeast from the Gulf of Mexico all the way to the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

“This is the last rock you’re going to see for eight hundred miles. From here on to the Gulf is the beach.”

The embayment is an anomalous dip in what used to be a mountain chain, and the fact that it overlays the New Madrid Seismic Zone is suggestive. One guess is that whatever drives the earthquakes pushed this section of mountains up, gave them time to erode, and then dropped them back down, leaving a big gap that then filled with sediment.

There's clearly something anomalous going on under all this muck.

Theories

There are so many theories! Everyone agrees that there's a weakness in the crust, and that it's incredibly old, a failed rift from Pangaean times. Why exactly this makes the earth shake is the vexing question. It wasn't long ago that this region was under glacial ice, so there has been speculation that isostatic rebound could be triggering earthquakes, the ground rising back up from under the crushing weight like a fat man's mattress. The Wabash seismic zone to the east is also suggestive—maybe the next big earthquake is actually going to be in Indiana? There's even evidence that the whole mess is the fault of an ancient subducted plate (possibly containing a cursed burial ground) wreaking havoc from deep within the mantle.

The boldest claim is that nothing is happening at all. Researchers who stuck a bunch of GPS antennas in the ground found no perceptible ground movement over nine years. Seth Stein published a paper arguing that the New Madrid quakes were the last of their kind, the final shiver of a dying fault complex, and that all of the small earthquakes on the fault since had been aftershocks from the massive 1811-12 events. The implication was that the government was now grossly overspending on seismic safety, cross-bracing the barn door after the horse was already dead.

More recent work has shown that New Madrid is still doing something; its current activity doesn't fit any model of aftershocks from the huge events three hundred years ago. Other researchers have stuck even more sensitive GPS antennas in the ground and found substantial evidence of creep, though what that actually means is anyone's guess. Even obvious assumptions about intraplate quakes, like the idea that strain accumulates with the passage of time, have not been proven.

With no physical model to go on, the study of these earthquakes is a carnival of curve-fitting. There are too many uncertainties in the uncertainties. Even papers that are skeptical of earthquake modeling end up smuggling Gaussian distributions and other simplifying assumptions in under cover of darkness, just to give themselves something to calculate.

The output of the process has to be a very clear answer—do we need to spend billions of dollars to save Memphis? Geologists have to walk a fine line between being intellectually honest and qualifying their answers so much they become useless.

Advance

What southern Missouri lacks in topography it makes up for in place names. I hate to go all Bill Bryson on you, but we pass signs for towns named Festus, Flucom, Knorpp, Puxico, Hayti, Armorel. Even the ordinary names are pronounced with an unexpected twist. New MAD-rid, CAY-ro. Prairie du Rocher rhymes with "kosher".

We make a brief detour to Advance (AD-vance) to see another invisible topographical feature left from the 1811 quakes. Geological writers are as persuasive as real estate agents when it comes to talking up a modest view. According to our tour pamphlet, “Quaternary history is shown in fluvial terraces, outwash plains, old channels, pressure ridges, and earthquake features.” If any of these are visible from the tiny bump of earth I'm balancing on, they are not visible to the layman's eye. A basketball dropped here might roll downhill, but you wouldn't need to break into a jog to retrieve it.

“Notice how you can see a tiny bit further from where we're standing?” Phyllis asks us. “This is a rise that parallels the fault system.”

“I think I see it,” says one of our geologists, unconvincingly.

You have to take what topography the Mississippi gives you. The river is a great eraser, whipsawing back and forth over the centuries to obliterate any mark.

We have penetrated deep into America's litterbox. Southeast Missouri is proud to be the world's leading producer of Fuller's earth, a material of many uses that millions of American cats poop into every day. There's a cat litter mine not far from Advance, and one presumes a dark but absolutely odorless bar filled with grizzled litter miners drinking away their retirement.

This portion of Missouri, along with northeast Arkansas, used to be impenetrable marshland, some of the last real wilderness in the central US. In the late 19th century local farmers hired diggers fresh off the Panama Canal to turn it into a giant putting green. These were men who thought in terms of "wasteland" rather than "wetlands", and had the machinery to do something about it. What they did is the largest drainage project in the world, the Little River Drainage district, which transformed this country from malarial swamp to a vast expanse of very lucrative nothing.

The keystone of the drainage district is an east-west ditch that shunts surface water to the Mississippi before it can flow any further south. Below that begins a series of north-south ditches that run parallel like pinstripes, slowly converging into a series of canals that empties into the St Francis river near the Arkansas border. The drainage system is still privately run (farmers pay dues by the acre) and the people who run it like to keep a low profile. They especially don't like to talk to visiting geologists about what an earthquake will do to their carefully terraformed irrigation sytsem.

It would not take a lot of ground movement to turn the bootheel of Missouri back into something resembling the Everglades. Drainage across the region depends on differences in height of a few feet. If it were up to Phyllis, she would keep heavy earthmoving equipment on permanent retainer. Preferably from several states away, maybe out in Kansas or Wisconsin. Not only will the bridges to the east be impassable, but you won't be able to find an excavator in all of Missouri for love or money in the aftermath of a large quake. I add ‘drive bulldozer to post-earthquake Missouri’ to my little notebook of get-rich-quick schemes.

Sikeston

From Advance we go to Sikeston. In 1931, J. Otto Hahs (1891–1969) invented and patented the coin-operated horse in Sikeston. In 1942, the last lynching in Missouri took place in Sikeston (hooray!) Downtown is a mix of bail bonds, pawn shops, dollar stores, seedy lawns and old, grand farmers' mansions from wealthier times. Around here the rule is if you have land you prosper, and if you don't, you eke out a precarious living as a laborer. The bootheel is the poorest part of Missouri.

Our first glimpse of Sikeston is a vast, ominous building with conveyor belts leading to pyramids of coal. Invisible under the corn stubble, but very clear on aerial photos, are the giant white polka dots called sand blows that mark places where soil turned to liquid in ancient earthquakes. The Sikeston city planners have built the power plant across one of the biggest ones.

Liquefaction wasn't understood until fairly recently, but it's one of the most damaging of earthquake phenomena. Seismic waves squeeze water into sandy layers in the earth, the sand loses its shear strength and turns into gravy, and the whole mess shoots out through weak spots in the overlying soil. The process in miniature is captured in a remarkable video from Tokyo during the 2011 Tohoku quake.

In places that are susceptible, liquefaction can cause massive property damage. Much of the destruction in Christchurch was a result of the ground flowing out from under buildings. Liquefaction is likely to be the star of any San Francisco earthquake, too. Residents will have the grim consolation of watching the Marina float like a river out the Golden Gate.

The telltale dots all over the soil testify to seismic history well before New Madrid. Sand blows in the region have been linked to earthquake events in 900 AD, 1450 AD, and 2350 BC (just to make them more mysterious, the quakes seem to occur in triplets). The sand blows are part of how we know that there have been regular earthquakes around New Madrid for at least the last ten thousand years.

New Madrid

In midafternoon we reach New Madrid proper. The little town sits at the top of an almost complete loop in the river. The original town is long gone; the 1811 earthquakes dropped the formerly high ground by fifteen feet, and two centuries of river flooding have finished the job. A big levee discourages the Mississippi from doing this again.

We drive through a subdivision of unremarkable little yellow buildings (brick facade on wooden frames, therefore fairly resilient, not that it would matter here) and stop at the town cemetery, a fenced-in vacant lot next to a playground. Kent Moran from the University of Memphis, an indefatigable seismic historian, is waiting for us at Eliza Brown’s tombstone.

Kent tells us how he found the tombstone face-down, had it cemented on to a large piece of marble, and embedded it in the ground. It has become, by an order of magnitude, the sturdiest structure in New Madrid.

Kent has spent years trying to piece together maps and earthquake timelines from two hundred years ago, a thankless task that he approaches with enthusiasm and skill. The better we can understand just how far each aftershock was felt, and how the larger quakes affected the landscape, the better our chances of modeling seismic hazard for the region. The large quakes of 200 years ago are our only window into how energy dissipates in this ground.

Kent is a master storyteller, so it takes a while to realize how incredibly painstaking and frustrating his work must be. Much of his current research revolves around making sense of older maps, to try to piece together just how much elevation change took place as a result of the quakes. Contemporary observers stressed how greatly the earthquakes affected the landscape, but quantifying that change is difficult and requires a frankly mind-numbing understanding of surveying practices in the Old West. Kent has a beautiful speaking voice, uncannily similar to Bill Clinton's when got something to apologize for, and you can listen to him talk about metes and bounds for hours. Looking at the notes I took later, I find they are completely impenetrable.

Kent explains the curious bootheel of Missouri. Locals were reluctant against having to wade through swampland to get to Little Rock to transact important business and demanded to be attached to Missouri instead. Today the drained land is "boring as a putting green".

It takes an effort of imagination to picture this place two hundred years back, not just because the river has moved, but because the whole vast territory was forest and in a twist of geopolitics belonged to Spain. The original settlement here bore the lovely name of Anse à la Graisse (Bear Fat Bend) reflecting the kind of commodities that were in top demand at the time. When the French secretly ceded the Louisiana territory in 1762, its new Spanish masters tried to lure settlers to the west side of the river as a bulwark against American expansion. One big draw was the promise of slavery. Slave owners worried about the Ordinance of 1787 freeing slaves northwest of the Ohio could just cross the river and swear allegiance to the Spanish king.

Colonel William Morgan formed the project of founding a major settlement here, and even came to lay out a street plan with his vanguard of settlers, but his plans were scotched when Spain secretly ceded the area back to France (secretly ceding territory was a big fad in the 18th century). The French barely had time to get their flag up before Napoleon sold the entire territory to the United States, and soon after that the New Madrid earthquakes made the whole issue of settlement moot for a long time. One nice side effect of the Louisiana Purchase was that it filled the region with overqualified civil servants sent in by Jefferson, who settled in just in time to witness the earthquakes. They are one reason we have unusually good reports of what happened.

Though it sits right on the Mississippi, New Madrid is hard to get to. It takes Kent four hours to drive from Memphis, the nearest major city. Someone asks how long residents can expect to wait before help reaches here if there’s a major quake.

“Seven days.”

Skittish people don't linger in New Madrid. The most pressing threat to the city isn't earthquakes, but flooding. The levee protecting New Madrid was built in 1927 and was nearly overtopped in the 2011 floods. If the levee is breached, the town will be on its way to New Orleans in about two hours. Through a perverse feature of the national flood insurance program, any land behind a 100-year levee is not designated floodplain, even if it's below the normal level of the river. There are no building restrictions whatsoever behind a levee. In the eyes of the law, it's as safe as the highest ground. People can build anything they like to while they wait for the 101-year flood, or the earthquake that will reroute the river.

The political system here is so broken that there's no hope of getting public agencies to work on preparedness. Missouri and Illinois state government is famously corrupt, and western Kentucky and Tennessee are not far behind. Like in so many places that only exist thanks to regulation and lavish government spending, there's a strong ethos here for deregulating everything. Structures in southeast Missouri aren't even required to be built to fire code; we pass a lot of burned-out buildings.

These earthquake tours arose partly out of frustration with government. Phyllis reasons that the way to get change to happen is by persuading those who stand to lose a lot of money—insurers, portfolio holders, anyone who owns substantial real estate. Beyond curious geologists, she tries to fill her bus with actuaries and regional insurance execs, scare them half to death, then release them into the wild so they can apply pressure to have strucutres inspected, upgraded, retrofitted, or just not built in the most hazardous locations to begin with.

The hard part about closing this loop is that the people who are most exposed to risk aren't the ones who would have to pay the bill. As the banking crisis of 2008 showed us, we treat sufficiently cataclysmic events as acts of God rather than failures of risk management. If enough people ignore a risk, they can successfully argue after the fact that no one could have foreseen it. Those who do prepare for diaster end up looking like chumps. Why act to mitigate a potential disaster when you know the rest of the country will bail you out?

We pay a visit to the New Madrid museum, which splits its attention between the earthquakes and the Civil War. The museum is run by a very friendly family, so we diplomatically overlook the fact that they've goosed the Richter numbers. The earthquakes were felt so far away that they were initially classified over 8.0, before people understood the physics of earthquake propagation and the amplifying role of sediment. A video from the eighties grandiloquently proclaims that New Madridians "have for two centuries endured hardship in settling a wilderness and forging a nation." Being diplomatic again, no one points out that they cut down the wilderness and rebelled against the nation.

The Civil War part of the museum promotes the "equal time" school of Civil War historiography that seems to particularly afflict the red states. According to this school, brave Americans divided into two teams and fought for five years over abstract principles of Constitutional law. Both sides had a good point—the North was right that allowing states to secede must eventually lead to anarchy, while the South was correct that it would be impossible to run a plantation economy without chattel slavery. The Civil War, therefore, was a tough call to make. Today we celebrate the heroes of both sides equally; their sacrifices helped us, as the movie says, forge a nation.

While there's nothing as egregious in Southern Missouri as Stone Mountain, I don't like that the losers of this war are given so much latitude in how to frame it. The more I see of Southern 'heritage', the more I develop a fondness for the old racist bastard William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman was awful in many ways, but he had strong feelings that you should fight a civil war in such a way to make it impossible to forget who won it. At the very least, Sherman would have called "no flagsies" on the Old Dominion, and spared us a century of Lost Cause mythologizing.

Kent is no apologist for the Confederacy, but he has his own reasons to dislike Sherman. On his march through the South, he burned an awful lot of archives and local newspaper bureaus, making it much harder to reconstruct the far-field effects of the New Madrid earthquakes.

Decked out in newly-purchased "It's Our Fault" t-shirts, we linger for a while on the city levee, secretly hoping there will be at least some kind of tremor while we're there. The last time Phyllis ran an earthquake tour there was a 5.1 quake in central Illinois, and the professor of emergency management felt the blood stir in his veins. But today we get nothing. The river glides by at a sleepy pace while the ground stubbornly stays put.

Rest Stop

Our final stop on the western side of the river is an unremarkable rest area on I-55. It got a windfall thanks to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and the state decided to spend the money on a seismic theme. Pillars outside show traces of a seismograph, while inside the floor has been laid out in a pretty mosaic map showing the geographic extent of the New Madrid quakes. It's a clever and imaginative redesign of what is usually a forgettable piece of highway boilerplate.

A member of our group who consulted on the project recalls suggesting to the planners that they leave one of the rest stop's brick walls half-finished, so that visitors can see the seismic reinforcement rods holding together the masonry structure from the inside.

There was a long, uncomfortable silence.

“What seismic reinforcement rods?”

This is a pattern with earthquake preparedness in Missouri. People mean well, but their hearts just aren't in it. Schoolkids practice hiding under their desks in buildings that would crush them.

We stop for the night in Dyersburg, Tennessee. Somewhere south of New Madrid we crossed the invisible line below which it becomes mandatory to serve biscuits and gravy at breakfast. You can get an unsweetened iced tea in Dyersburg if you ask for it, but there's a pause to assess if you're being serious. I imagine this is what it's like to order decaf in Seattle. The tea arrives marked with a long spoon and a lemon wedge, the lemon wedge as a warning to others, the spoon so you have something to stir the sugar in with when you come to your senses.

Reelfoot Lake

Heavy with gravy, we start the next day with a visit to Reelfoot Lake, the most beautiful landscape of the whole tour.

Reelfoot lake is another gift of the 1811 quake, which took this formerly boggy ground and dropped it by several feet. It is the last undrained lake in this part of the country, and not for want of trying. The underlying land would be so valuable that people actually fought a miniature war over land rights under the lake in the early 20th century, until the courts decided that a lake extinguished all land claims underneath it.

Today Reelfoot Lake is a Mecca for fishermen, who come from all over to fish for crappie (pronounced croppy). The place oozes Americana. The piers are thick with dads taking their freckle-faced boys fishing, while old-timers in straw hats recline in folding lawn chairs set back from the boardwalk. Bald eagles—really—perch on top of some of the taller cypress trees. Across the road from the park entrance is a fireworks stand. A Confederate flag flies discreetly in the distance.

We are a little giddy with topography today. Unlike the west side of the river, the east bank has hills and bluffs. Some of it is crumbly material called loess, windblown dust from the Great Plains that settles and accumulates in great layers east of the river. Loess is responsible for the greatest body count in any known earthquake, the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake. Fortunately no one over here is living in frangible dust caves.

Hickman

We pay a brief visit to Hickman, Kentucky, one more riverside town that had its plans for the future vetoed by the Mississippi. The older, lower part of Hickman never recovered from the flood of 1927, and stands abandoned. All the action is in upper Hickman, built on fragile bluffs that yearn to slide into the river at the next big rainstorm. Hickman is not giving up this time without a fight.

At vast expense, these bluffs have been stabilized and entombed in a sarcophagus of riprap, shotcrete, and chain link. So confident is Hickman in its victory over nature that they've built their emergency services—along with two massive water towers—right at the lip of the structure. I am all about respecting people's connections to the land, but it's also worth considering the land's connection to the land, or in this case, the land's clearly expressed desire to slough off and seek a permanent home in the Gulf of Mexico. Sometimes you just have to let it go.

But Hickman doesn't want to let go, and has powerful friends in the Senate. This structure is western Kentucky's version of the famous 'bridge to nowhere', a pointlessly expensive infrastructure project that makes no economic sense but brings money to a valued political district. Mitch McConnell wants to keep Hickman happy.

This is how it works along the Mississippi, where the twin weapons of preparedness are massive earthworks and denial. If seismic retrofitting involved more bulldozers, it would be a lot easier to get it funded.

The Fault Scarp

Just before noon we reach the geological climax of our trip, the actual New Madrid fault scarp near Tiptonville. The same great jolt that sunk Reelfoot Lake elevated a long ridge of land closer to the river, pushing it up by ten meters. By local standards it should look like the Himalayas.

We arrive on a straight stretch of road between two cotton fields. The stop sign at the end has been pockmarked by bullets. Our professor of emergency management, a quiet fellow who knows his guns, points out that they're from automatic rifle fire. Welcome to Kentucky! It is a very beautiful day, and the landscape before us bears an uncanny resemblance to the Windows XP home screen.

We stand beside the road staring at the one unequivocal mark of the New Madrid earthquakes, left from two hundred years ago. Mighty tectonic forces thrust this land above the earth and have left it as a warning and a monument to the ages. A few minutes pass as we take in the gravity of where we are.

“I’m sorry, which exactly is the scarp?” asks our geodynamicist, a little sheepishly.

“It’s that ridge-like feature right there. basically the horizon. It’s a little hard to see.”

“There with the gravel road on it?”

“No, that’s the levee. But the Corps of Engineers built the levee right up to the scarp. They like to economize.”

“So it's that kind of culvert thing of in the middle distance?”

“No, up past that. You see the three houses there on the horizon?”

“Yes.”

“That's the scarp. They've built them directly on top.”

Columbus

We eat lunch at Columbus State Park in, Kentucky, the so-called Gibraltar of the West. The Confederates under Polk occupied this high ground early in the war and ran a chain across the river to thwart Union gunboats. In an un-Gibraltar-like move, they relinquished the position without a fight in 1862.

The Army has not let go its hold on the river. The Corps of Engineers approaches river management in a suitably martial way: they build giant fortifications, blow things up, and produce heartfelt and agonizingly square propaganda about why taming the river is the right thing to do.

There is a pretty view of the river here, and we can see the massive amount of barge traffic that goes through. Misissippi barges are hefty rectangles full of commodities pushed at the downstream end by a confusingly-named tugboat. Corn and soybeans move downstream; fertilizer, coal, lubricants and scrap metal move upstream. Unlike rail or road transport, barge traffic is almost entirely subsidized by the nefarious Federal government, who pays the cost of dredging and shaping the river. Like cosmetic surgery, these interventions get more drastic and less effective as time goes on.

In addition to the levees along the river's length, the Corps also operates a complex set of locks on the upper Mississippi, and builds ever-larger earthworks at the mouth of the Mississippi to keep the river (which desperately wants to flow down the Atchafalaya) running past New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

Cairo, IL

Illinois law generally forbade bringing slaves into Illinois, but a special exemption was given to the salt works near Equality. - Wikipedia

Just as the Colorado river runs out of water before it reaches the sea, money in Illinois runs out before it can get to Cairo, at the southern tip of the state.

The actual southernmost point of Illinois is a state park that lies outside the levee and is slowly reverting to forest. Cairo greets us with a pair of billboards bleached almost to white. The town center looks like it got hit by a neutron bomb in 1968. Weeds grow unchecked among abandoned storefronts. A few of the brick facades have even started collapsing into the treet. Some invisible ghost of civil government has carefully marked a pile of fallen bricks with a traffic cone.

If you were playing a game of Civilization on blank map of the United States Cairo is the spot you would pick to build your first village. The town sits on a triangle of land at the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, gatekeeper to the American interior. It's the most obviously central place in the central United States.

Had the town been thirty feet higher, it might have become a city to rival Memphis or St. Louis. But Cairo lies low to the ground between two outer bends in the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. The two rivers want to close up on Cairo like a zipper. When the water is high, the town threatens to flood from three directions at once. The surrounding rivers don't defend Cairo so much as menace it.

When the railroad came, the same rivers that made Cairo strategically important became an inconvenient obstacle. But what really doomed the city was racism. Southernmost Illinois is culturally a part of the South even though it's on the Union side of the Ohio River. The civil rights movement here took the form of a pitched battle (without exaggeration) between black residents and white merchants who refused to serve them. Someone decided to build a multi-story public housing project into the side of the levee and force the town's black population people to live there. When the Interstate came through, the powers that be made sure to pass Cairo by.

"Any possible hope for moderation disappeared in 1971, when members of the United Citizens for Community Action (UCCA), an affiliate of the White Ctizens' Council, gained control of the city council.19 During this period [1971] there were some thirty-seven fires of suspicious origin and over 140 days of shooting. It appeared that the white community would suffer bankruptcy or even total annihilation of the town rather than try to come to terms with the black community."

The ghosts of slavery are everywhere on the Mississippi. The levees on the lower Mississippi (including those around Cairo) were built by slave labor. The malaria and yellow fever that made so much of the American South uninhabitable came over on the same ships as West African slaves.

What sets Cairo apart from the other failed towns on the Mississippi is how far it's fallen. Like Detroit, it's a favorite for documentarians of the dying American city. I feel ill-at-ease being a disaster tourist, but this is something unique in my experience of America. Cairo is the husk of a town that was going places, a town that could have been a contender. The broad avenue of mansions down the main street isn't something you usually find in a derelict city.

The most recent example of how little people care about Cairo came in 2011, when high water threatened to overtop the levee. The Corps of Engineers made provisions to open the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway, a structure designed for this exact purpose, but they were sued by Missouri farmers (who, let me stress, were raising their crops on something called a floodway). The farmers argued that Cairo was worth less than the acreage that would be inundated to save it. This accurate statement tells you everything you need to know about property values in Cairo, and the spiritual values of the southern Missouri farmer.

The case went to the Supreme Court, the Corps of Engineers filled the white plastic pipes in the levee with explosive slurry and blew the levee, and Cairo held. The farmers downriver got their fields fertilized with rich river silt and are wealthier and more resentful than ever. Like so many beneficiaries of big government, they remain its implacable foes.

If I go on about this stuff, it's because the flaw at the heart of our country is not just geological. There's some connection between our inability to confront our past and the refusal to think rationally about the future. These pockets of poverty and despair, so often black poverty, are not an accident of history. They form a vast, second-tier America that we've simply written off for good. In places like Cairo, Fresno, Flint, Gary, Camden, Detroit, Baltimore, the cities of upstate New York, the Indian reservations of South Dakota, Appalachia, a slow-motion disaster has been taking place for decades. There's no need to wait for an earthquake.

At the entrance to Reelfoot Lake I saw a plaque explaining that the lake had been cleared and made accessible through the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was a Depression-era project to give young unemployed men useful work to do at a living wage. It offered hard-up people a sense of dignity and purpose, a way to feed their families, and made a lasting ecological impact across the United States.

Today such a combination of environmentalism and federal spending would be unthinkable. Only the Army can mobilize hundreds of thousands of young men and women and be immune from the charge of socialism. And the Army guards the levees while leaving the communities behind them to rot.

The idea that the concept of national security could include natural disasters is too radical for any American politician. Even in California, where the memory of recent quakes is freshest, it's impossible to find funding for proven safety measures like an early warning system. Cell phones are rigged to wake us up if a child is abducted, but not if the roof is about to fall in.

A few years ago I had reason to visit a tiny Norwegian town called Burfjord, a provincial town marooned just inside the Arctic circle. Years from now, when I am on my deathbed reliving scenes from a life richly lived, it's not going to be Burfjord on my mind. It's a remote, unlovely community, a vast distance from any major population center, with little economic basis apart from logging and fishing, in a country that does not really want for logs or fish. But the Norwegian attitude is, we are Norway, this is one of our towns, and by God we are going to make it look like Norway.

And so Burfjord has a lovely library, freshly-paved roads, decent medical care, a nursing home, a cultural center. Most of the 397 people in Burfjord are employed by the government, making sure the lives of the other 396 Burfjordians are up to a Norwegian standard. Since Norway is packed with Burfjords, the arrangement costs the government a fortune. But it's just part of the accepted cost of being Norwegian.

This kind of ornery civic-mindedness doesn't exist in the United States. I wish it did.

I went into this trip expecting to be pleasantly titillated by the prospect of a New Madrid earthquake. Instead, I came out of it a seismic radical. Earthquakes are one of the last truly democratic institutions left in America. Let's give them a chance. Like Phyllis suggested, nothing too fatal, nothing too costly, but something big enough to wake people up. Nothing else seems to be working.

(I'd like to offer warm thanks to Phyllis Steckel, Mellisa Lenczewski, Kent Moran and the other participants in the tour for graciously allowing me to tag along and ask endless questions.)